I have a major new paper coming tomorrow on sexual selection in dinosaurs. This is an area in which I have been extremely heavily involved in the last decade and have published numerous papers on this subject with various colleagues, writing about the underlying theory of sexual selection and how it might appear in the fossil record, providing evidence for it and actively testing hypotheses. This has also led into my working on related issues of ontogeny and social behaviour in dinosaurs which feed back into these areas to try and deal with certain aspects that came up as a result of these analyses.

Suffice to say I’m not going to go back over the whole history of my work in the field, or that of plenty of other researchers which is both relevant and important. But a little bit of context is important with respect to the coming paper because it’s something that I’ve had in my mind to do for about as long as I’ve been working on this subject but I didn’t think I’d be able to do because the dataset didn’t exist.

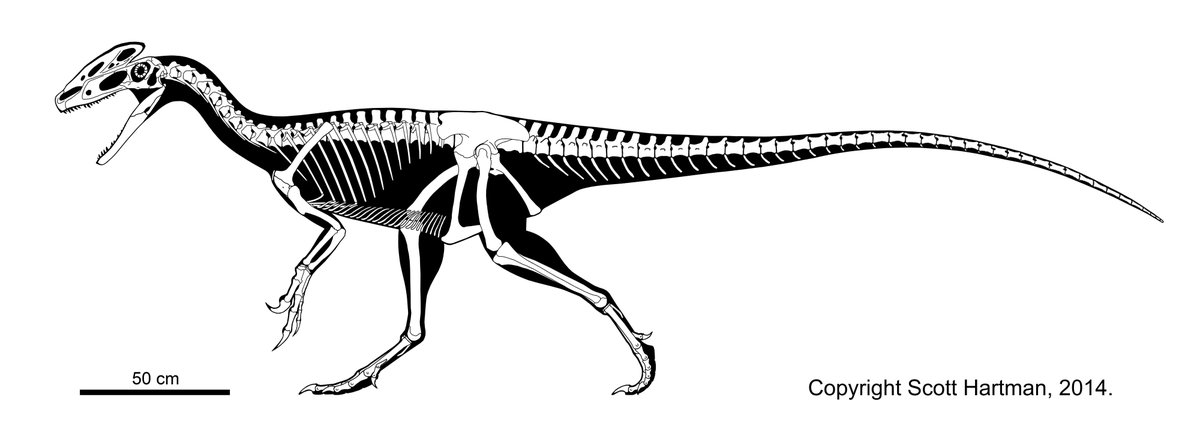

All of the work I have done really tried to get into answer the questions of which features of which dinosaurs may have been operating under sexual selection and can we tell. (More properly, I should say socio-sexual selection since teasing out social dominance signals from sexually selected signals is probably impossible though mostly the two are more or less synonymous in various ways so it’s not a major issue conceptually). The short answer is that really quite a lot of features probably are under some form of sexual selection. We can see this by the fact that we can rule out functional explanations for things like ceratopsian crests as being anchors for muscles attachments, radiators, or for defence because they are highly variable and / or fundamentally don’t work (Elgin et al., 2008; Hone et al., 2012). They are costly traits to grow and lug around (be they stegosaur plates or hadrosaur crests) and so clearly have a fitness cost, ruling out species recognition as a signal (Knell et al., 2012; Hone & Naish, 2013). Similarly, there is no clear pattern of differentiation among sympatric species as would be critical for a recognition trait (Knapp et al. 2018). They are highly variable both within and between species, another hallmark of sexually selected traits (Hone & Naish, 2013; O’Brien et al., 2018) and finally they grow rapidly as animals reach sexual maturity which is absolutely characteristic of sexual selection (Hone et al., 2016; O’Brien et al., 2018).

The one issue that has remained elusive in all of this is the vexed issue of dimorphism. This has proven very hard to detect for a variety of reasons, but most notably the generally small sample sizes we have for dinosaurs and the tendency for males and females to overlap in size and morphology over much of their lifespan (Hone & Mallon, 2017). To top it off, mutual sexual selection can reduce or even eliminate dimorphism making it harder still to detect and meaning even an apparent absence of it, does not mean sexual selection is not in operation (Hone et al., 2012).

It would be nice to be able to explore the issue of dimorphism in particular in more detail with an extant analogue. Plenty of comparisons have been made to various living taxa in terms of dimorphism (be it body size or major features like a crest or sail) but they run into various issues. Mammals are nice and big and often have things like horns that differ between males and females (either in shape or presence / absence), but they’re phylogenetically very distinct and have the problem of growing quickly to adult size and staying there. Lizards offer something interesting with some dimorphic species with various signal structures (like some chameleons) but then while they are reptiles, most are small and the biggest varanids have no sexually selected structures. Birds are obviously literally dinosaurs but have a mammalian-like growth and are not very big. While there’s plenty of size dimorphism in them, there are few that have obviously dimorphic traits that would show up in the skeleton (like horns).

That leaves the crocodylians, which are off to a good start. Some are very large and take a long time to grown to adult size, all are egg layers, they are sexually mature long before full size meaning they would likely express sexually selected traits while still quite small (like dinosaurs and unlike birds or mammals), and a number are also sexually dimorphic in body size. The only thing missing is some kind of sexually selected bony feature, or at least one with a clear osteological correlate.

And so to the gharials, the wonderfully weird crocodylians of the Indian subcontinent which tick every single one of these boxes right down to the growth on the snout of males, the ghara, that is absent in the females. This has long been obviously the one taxon that ticks pretty much every possible box and would provide an excellent living model to analyse and see how easy (or not) dimorphism is to detect when you have a known dataset to work from. The obvious limit to this plan is that these animals are extremely rare and most museums have few, if any, specimens. The one species that was pretty much perfect for my plans immediately fell out of contention because I couldn’t see how I could get a dataset together that would be sufficient for analysis, so the idea was shelved. Until recently…

Obviously, to be continued.

Papers on sexual selection, dimoprhism, socio-sexual signaling, social behaviours and related subjects in fossil reptiles:

O’Brien, D.M., Allen, C.E., Van Kleeck, M.J., Hone, D.W.E., Knell, R.J., Knapp, A., Christiansen, S., & Emlen, D.J. 2018. On the evolution of extreme structures: static scaling and the function of sexually selected signals. Animal Behaviour.

Knapp, A., Knell, R.J., Farke, A.A., Loewen, M.A., & Hone, D.W.E. 2018. Patterns of divergence in the morphology of ceratopsian dinosaurs: sympatry is not a driver of ornament evolution. Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series B.

Hone, D.W.E., & Mallon, J.C. 2017. Protracted growth impedes the detection of sexual dimorphism in non-avian dinosaurs. Palaeontology, 60: 535-545.

Hone, D.W.E., Wood, D., & Knell, R.J. 2016. Positive allometry for exaggerated structures in the ceratopsian dinosaur Protoceratops andrewsi supports socio-sexual signaling. Palaeontologia Electronica, 19.1.5A.

Hone, D.W.E. & Faulkes, C.J. 2014. A proposed framework for establishing and evaluating hypotheses about the behaviour of extinct organisms. Journal of Zoology, 292: 260-267.

Hone, D.W.E., & Naish, D. 2013. The ‘species recognition hypothesis’ does not explain the presence and evolution of exaggerated structures in non-avialan dinosaurs. Journal of Zoology, 290: 172-180.

Knell, R., Naish, D., Tompkins, J.L. & Hone, D.W.E. 2013. Is sexual selection defined by dimorphism alone? A reply to Padian & Horner. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28: 250-251.

Knell, R., Naish, D., Tompkins, J.L. & Hone, D.W.E. 2013. Sexual selection in prehistoric animals: detection and implications. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 28: 38-47.

Hone, D.W.E., Naish, D. & Cuthill, I.C. 2012. Does mutual sexual selection explain the evolution of head crests in pterosaurs and dinosaurs? Lethaia, 45: 139-156.

Taylor, M.T., Hone, D.W.E., Wedel, M.J. & Naish, D. 2011. The long necks of sauropods did not evolve primarily through sexual selection. Journal of Zoology, 285: 150-161.

Elgin, R.A., Grau, C., Palmer, C., Hone, D.W.E., Greenwell, D. & Benton, M.J. 2008. Aerodynamic characters of the cranial crest in Pteranodon. Zitteliana B, 28: 169-176.

Recent Comments