So yesterday at short notice I rushed up this teaser post which seemed to do the trick, and now I’ve got a bit more time on my hands, I can start putting down a proper post on the subject. Yep, I have a new paper out and this time featuring dromaeosaurs and pterosaurs. Long time readers will remember that almost exactly 2 years ago I had another paper out on dromaeosaur scavenging featuring shed teeth and bite marks on some Protoceratops material. Coupled with the famous fighting dinosaurs specimen we have pretty good evidence for dromaeosaurs, and specifically Velociraptor for feeding on this dinosaur. The record of dromaeosaur predation and feeding is actually pretty good compared to other theropods groups and there is also an isolated pterosaur wing bone from Canada with shed dromaeosaur teeth and bite marks.

This ‘new’ specimen marks the first record of gut contents for Velociraptor and the first record of a pterosaur bone as gut content in a theropod. (The ‘new’ is becuase this specimen was actually found in the 1990s, but has yet to be described, though I’m told there’s a photo of it in Luis Chiappe’s recent birds book). Thus we do have rather exceptional evidence for a Velociraptor chowing down on an azhdarchid.

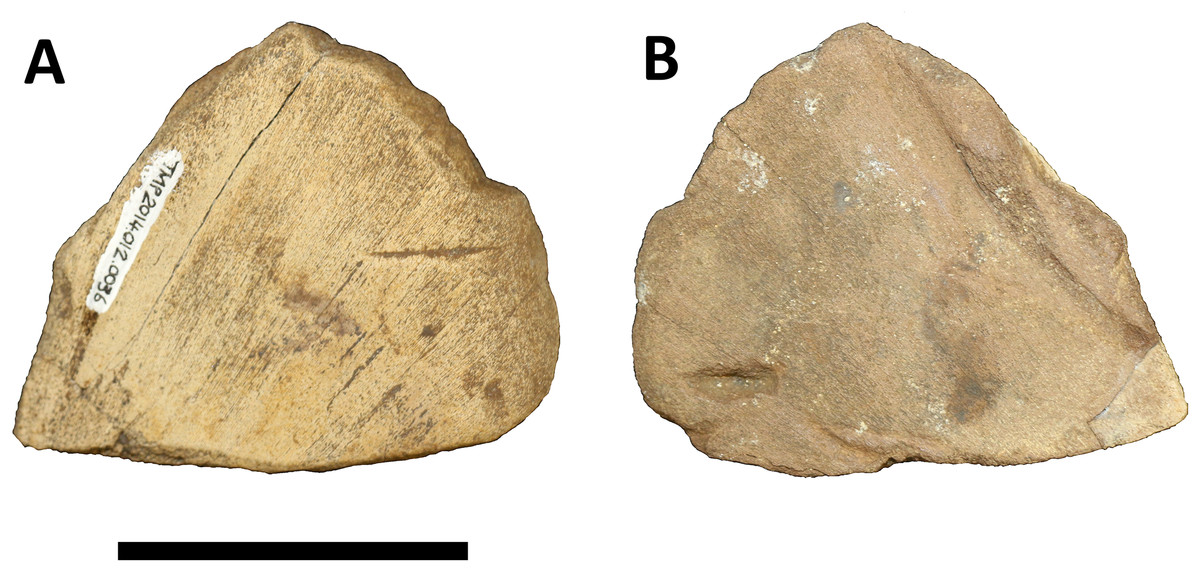

And here it is, well part of it. The Velociraptor in question was remarkably well preserved and complete which allowed the preparation of it with the chest cavity as a single articulated piece with the vertebrae, sternum, ribs, gastralia and even uncinate processes all intact and in their original positions. The bones are really well preserved and much of the material has been prepared free of the matrix entirely. One obviously example is the skull which, bizarrely, is on display in Barcelona so at least some reader might have already seen that, though sadly I haven’t and had to rely on some superb photos kindly sent by Fabio Dalla Vecchia. It’s hard to show the bone off properly what with the whole ribcage in the way (which is, incidentally, a broken ribcage, one of the ribs took a huge battering and shows a healed break – white arrow in the above picture). S you’ll be delighted to know there are also some close-ups in the paper like this one (below) and even some CT scans in the supplementary data.

As you can see the bone is incredibly thin-walled which is the major reason that it’s inferred to be an azhdarcid pterosaur, though their presence in the Late Cretaceous, including a related formation, and the general absence of other pterosaurs in the Late Cretaceous helps support this identity. Given what is around and the thinness of the bones, it’s pretty unambiguous as indeed is the identification of the dromaeosaur as Velociraptor given that we have basically the whole thing. In short, this is about as convincing a case as one could make that a Velociraptor had eaten an azhdarhid. But was it really scavenging? Well that and other issues I’ll be talking about tomorrow, as there’s quite a lot more to say on this. Stay tuned.

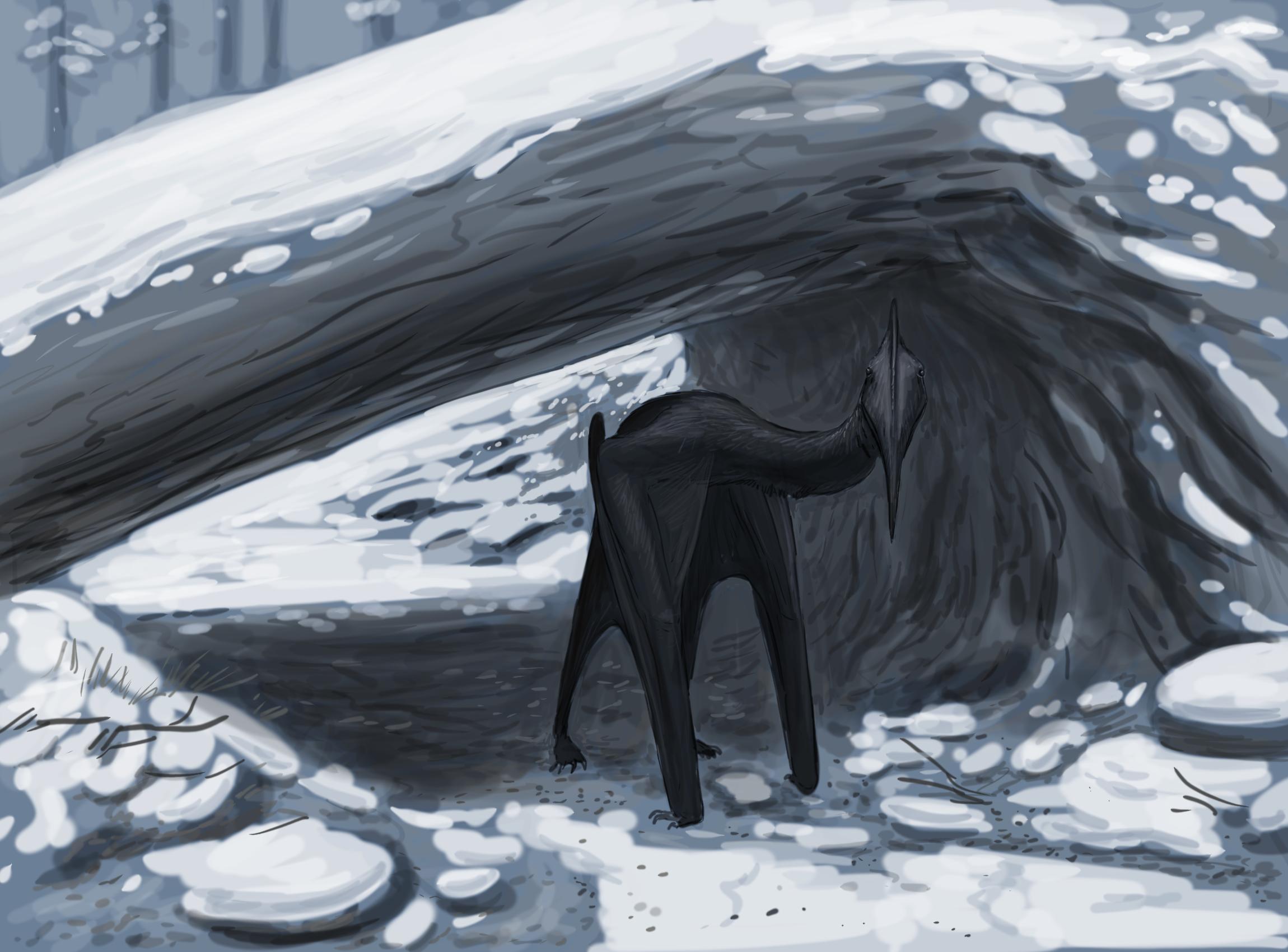

Finally, my thanks to Brett Booth for more awesome artwork for me to use, and you can see more of this and my interview with him on his dinosaurs here.

Hone, D.W.E., Tsuhiji, T., Watabe, M. & Tsogbataar, K. Pterosaurs as a food source for small dromaeosaurs. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, in press. Horrible uncorrect proof and behind a paywall, but the abstract, figures and other bits are visible to all.

Recent Comments