To those interested in palaeoart and the world of dinosaur reconstructions, the name Jez Gibson-Harris might not be familiar at all, and yet I can guarantee that almost everyone reading this has seen a number of his models and puppets since he and his crew put together all the live-action animals used in Walking with Dinosaurs and various subsequent sequels (and you’ll also know his work from the Dark Crystal not to mention Star Wars). Jez was kind enough to answer some questions about building model dinosaurs and getting them on screen, and he also handed over a nice pile of photos of various creations for me to share (though as ever, please don’t use these without his permission).

What is your background in model making?

I always made stuff when I was young, kits, sculptures, toys, jewellery then at College in Richmond in the late 1970’s I did a one year Art foundation course: so much fun, so many different techniques to experiment with. I then started a Jewellery and Silver Smithing course which I left after a couple of terms and joined a special effects makeup company that had just finished working on The Empire Strikes Back. I worked on The Dark Crystal and Return of the Jedi, building the famous Jabba the Hutt and later worked on Greystoke the Legend of Tarzan, The Never Ending Story 1 & 2, Willow, Tomorrow Never Dies and many more.

In 1986 I set up Crawley Creatures Ltd. in the Oxfordshire village of Crawley near Witney with a partner, Nigel Trevessey. We worked closely with Oxford Scientific Films working on Natural History films, documentaries and commercials and made models and animatronics for commercials and TV shows all over Europe. Nigel returned to freelancing in 1992 and went on to supervise the fantastic model build of Hogwarts for the Harry Potter films.

How did you get into recreating dinosaurs and prehistoric animals?

In 1996 I was approached by a BBC researcher to make a pilot documentary film for ex-Horizon Producer, Tim Haines. The pilot was Walking with Dinosaurs. We built a couple of maquettes a half scale Liopleurodon head and close-up body parts, including a large pair of feet to make footprints.

Tim Haines documentary background and exacting standards ensured that the real, grassless, backgrounds, the animatronics, models and CG all worked together to create a truly believable natural environment. The series was one of the most popular TV programmes at the time and won multiple awards including a Millenium Products Award, an Emmy and Baftas.

The success of this series spawned a genre of programmes over a ten year period depicting early life; Walking with Beasts, Ballard of Big Al, Sea Monsters, Walking with Early Life, The Giant Claw, Walking with Giants and Prehistoric Park. We also worked on the first three series of Primeval and more recently on Prehistoric Autopsy with Dr. Alice Roberts.

We made a T. rex head for a TV pilot of the Lost World, when we worked ay OSF, the series started at Pinewood Studios but was cancelled after six weeks into the build. I think our link with documentaries and OSF and our background of realistic looking work got the attention of the BBC researcher and as is often the case with the TV and Film industries you get pigeon holed, but what a nice area to get pigeon holed into!!

I am fascinated by natural history and paleontology, I have always loved museums, so much so that I have now designed a range of fossil chocolates (I have to admit that I love chocolate just as much as dinosaurs!). So we do a lot of dinosaurs for museums now as CG takes over more of the film and TV work. We have worked for The Natural History Museum London, Oxford University Museum (my favourite), The Eden Project, Gondwana das Prehistorium in Reden, Saarbreuken, Germany and the yet to be opened Dinosauropolis in Athens.

How do you start a new animal?

Usually we will receive a brief from an Art Director and we will do our own research for the latest museum reconstructions, or artists visuals, trips to museums to photograph fossils or skeletal reconstructions. We have a library of books that utilise as well as looking at internet sources.

A production company will usually have a researcher available who will look for the most recent scientific papers and studies and look to key palaeontologists whose field the beast we are reconstructing falls into, to provide us with feed back to images we send as we start to build our creatures.

What are the major techniques that you use?

We will start off with an armature, usually a metal framework, covered in chicken wire, hessian scrim and plaster all coated with shellac. The armature will be smaller than the intended finished surface, allowing for a layer of water based clay or wax based modelling material that will be sculpted to the smooth or wrinkled and textured skin surface that is required.

If we are making a large creature or model, we will usually sculpt a smaller scale maquette, (usually 1/10th scale). The maquette will enable us to create the pose and proportions of the creature quickly and get feedback from our client and any scientific advisers before the full scale figure is tackled.

When making a very large model we have the facility to laser scan the maquette, surface the scanned data in GeoMagic software, which allows us to manipulate the model in CAD. These files can then be sent to a 5 Axis machining company where we can get a full sized armature machined in polystyrene.

When the full sized armature is returned to us we can then begin the clay sculpture. The finished clay surface is then sealed and a GRP (glass reinforced plastic) layer is applied, usually the mould is made in several joining sections and once cured this will for a hard jacket mould that will have all the surface texture from the sculpture embedded into its surface. When the mould has cured the parts are removed and cleaned and the sculpture is destroyed. Casts are taken from the mould in various flexible elastomers such as silicones or polyurethanes.

What do you have to consider from scientific sources and how do you decide where there in uncertainty such as with colours?

We will always aim for our models to be the best and most up-to-date reconstructions around so we encourage critical feedback especially at the sculpture stage when it is relatively easy to make alterations. We will produce a colour scheme based on discussions and this will be changed until an agreement is made.

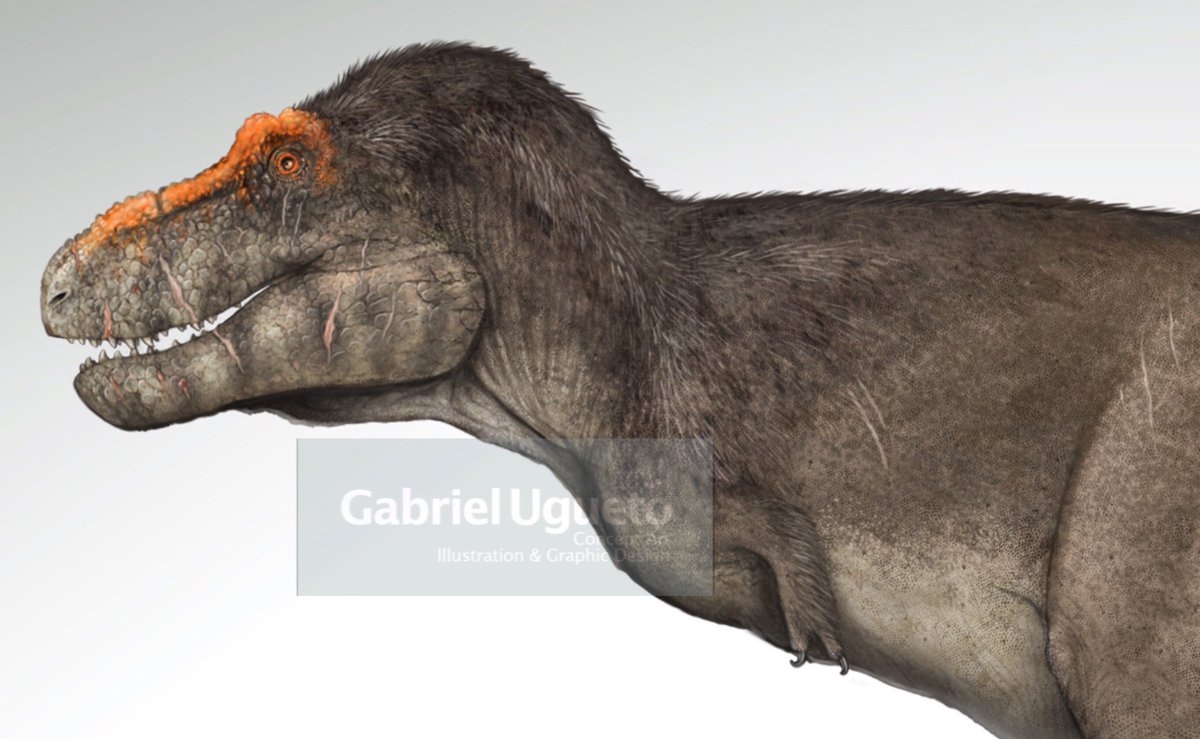

Skin texture, colour schemes and feathers etc. on dinosaurs are tricky, there is no information on colour or sounds or behaviour and scant fossil evidence, as far as I am aware, of skin texture and feathering on larger specimens.

Scientists are able to argue the case for their views and understanding as to what the colour, feathering styles etc. may have been but from a filmic or TV point of view a creative decision has to be made to get the visuals on the screen and it is often a ‘best guess’ approach. The ‘best guess’ decision will usually be based on a modern analogy of the creature, our understanding of the environment that the creature may have lived in, whether the creature is a herbivore or carnivore, it’s size, whether the creature is bird, reptile, marine-reptile or crocodile like in its make-up, all this will be factored into the decision.

What to have to consider from the perspective of filming?

Time is usually very short on a production so after discussions and hopefully a story board from the production company, we know exactly what we need to build and what the camera will need to see. Time and materials are very expensive so ideally we will only build what needs to be seen which is why a storyboard is so important. Sometimes we can build models to a smaller scale if there is no referenced give away in the shot. If we are filming at a studio or on location we have to think ahead about logistics of moving a large model or for freighting and crating and the logistics of moving and operating in the environment on the shoot

How many people would be involved in a typical build?

Because of the nature of the contacts for film, TV and museum work the deadlines are usually very short and labour intensive. So, as well as using our fulltime staff we rely on a network of Freelance Specialists to assist in delivering the models to the screen.

At present we are building a well known, very large, full-sized creature. We have three sculptors, seven mould-makers a mechanical engineer, and a CAD engineer in addition to the two office staff. Shortly we will be hiring two body fabricators. Fabricators really make soft mechanics, using specialist foams and lycra fabrics they will design and make a flexible under-structure that the sculpted skin surface will attach to, but still enable the skin to bend and flex realistically in all the right places, similar to the under-structure of costumes used in programs such as the Telly-Tubbies and their ilk.

Later in the process we will bring in a couple of Art-Finishers to prepare and then paint the assembled finished creature skins.

What is the creation from your team that you are most proud of?

This is a difficult question for many reasons. One of my first jobs in the industry was working for the Jim Henson Company on the film the Dark Crystal and I was making Mystic characters. The team of people we were working with was so creative and exciting that I will never forget it.

Jabba the Hutt has to be one of my best achievements, working with a small team of six people we made one of the most famous villains in cinema and for such a prestigious film, I still get asked for autographs by Star Wars fans.

Greystoke was my next film and our supervisor Rick Baker won an Oscar for the work we all contributed to. The quality of the ape suits and the performances of the costume wearers was very special.

But those three films were in my freelance days and so the creations I’m most proud of from Crawley Creatures point of view is the work we produced for the BBC/Discovery Channel series of Walking with Dinosaurs. It was a very bold concept at a time when animatronics and CG had not been used a great deal in TV. With a small budget, from a special effects point of view, a very small build crew and production crew we felt very much part of the whole process from start to finish and that involvement was very creatively rewarding. The series was a huge worldwide hit and it got a lot more people very interested in dinosaurs and we won several awards for our work, which was nice!

Recent Comments